Many of the principles in Behavioural Science directly contradict one another.

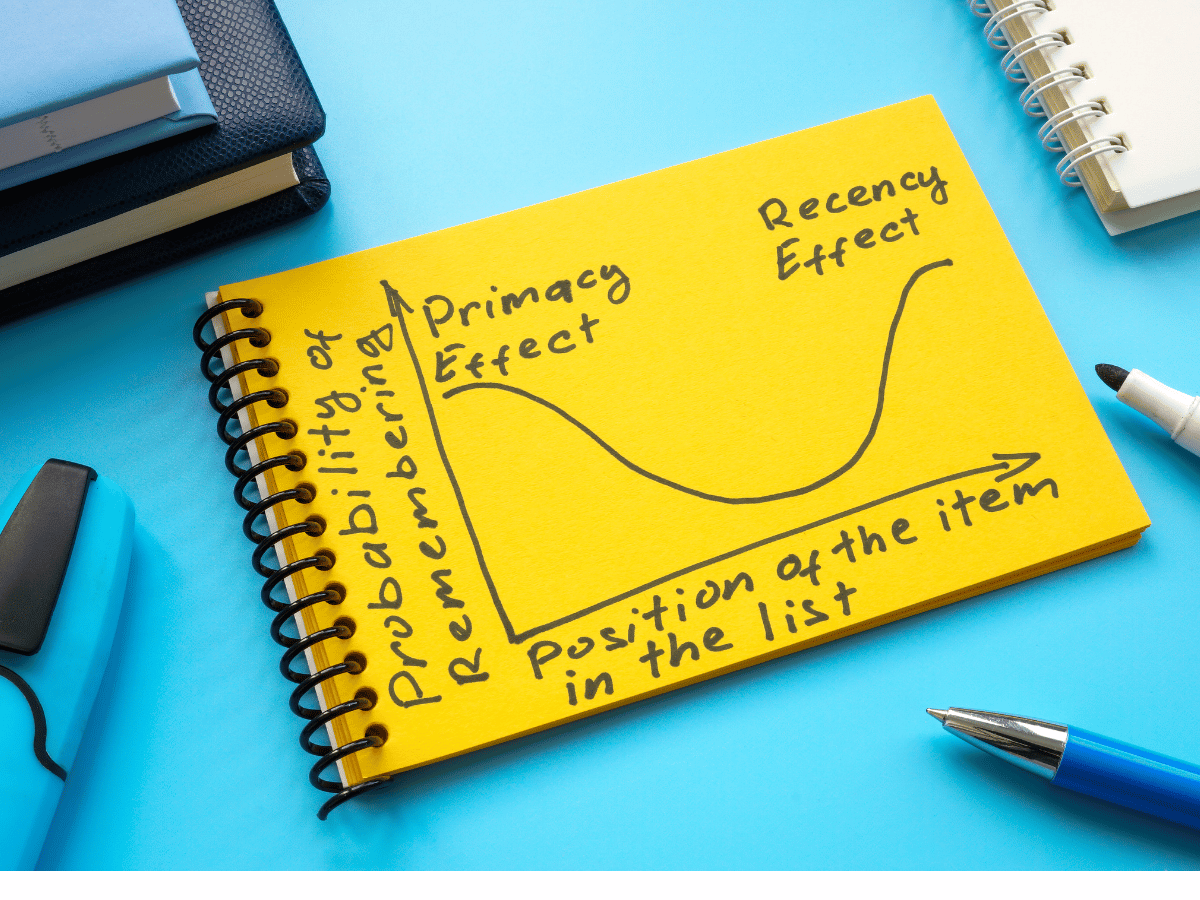

– Are we more likely to remember the first word on a list (primacy) or the last word on a list (recency)?

– Do we prefer trying a new restaurant for dinner (novelty) or sticking with our local favourite (status quo)?

– Does repeatedly hearing a false statement make us believe it (illusory truth effect) or reject it (backfire effect)?

Bothism

In a world of binary thinking, we forget that opposites can co-exist.

They are largely contradictory:

– Absence makes the heart grow fonder / Out of sight, out of mind

– A stitch in time saves nine / Haste makes waste

– All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy / Idleness is the devil’s workshop

– Birds of a feather flock together / Opposites attract

– You can’t teach an old dog new tricks / Never too old to learn

– You can’t tell a book by its cover / Where there’s smoke, there’s fire

– Better safe than sorry / Nothing ventured, nothing gained

– He who hesitates is lost / Fools rush in

– Two heads are better than one / Too many cooks in the kitchen spoil the broth

The director David Fincher shoots upwards of 70 takes for certain scenes, insisting that actors require to loosen up and get into character. Meanwhile Clint Eastwood tries to use only one take per scene if possible, trusting his cast and his crew to provide what they’ve been hired to provide. Neither technique is objectively better or worse – they just suit different needs. After all, both directors are celebrated Oscar winners.

Steven Spielberg has made a blockbuster in almost every single genre: science fiction, war, historical drama, fantasy, horror. Meanwhile, Alfred Hitchcock, the master of suspense, became Britain’s most celebrated director by sticking to one.

Until the mid 2000s the Premier League was dominated by two managers – Arsène Wenger and Sir Alex Ferguson – who collectively won 11 of 12 titles. But their managing styles couldn’t have been more different. Wenger would stay silent for the majority of the half time break, believing that players needed to calm down before they could think and communicate clearly. Meanwhile Ferguson was synonymous with the ‘hairdryer treatment’ – screaming at players, and in one instance kicking a boot at David Beckham’s head.

Some of the greatest artists in history – Picasso, Woody Allen, Kanye West – do things that are morally (and legally) wrong. Should we think of them as good or bad? In many cases, the answer is both.

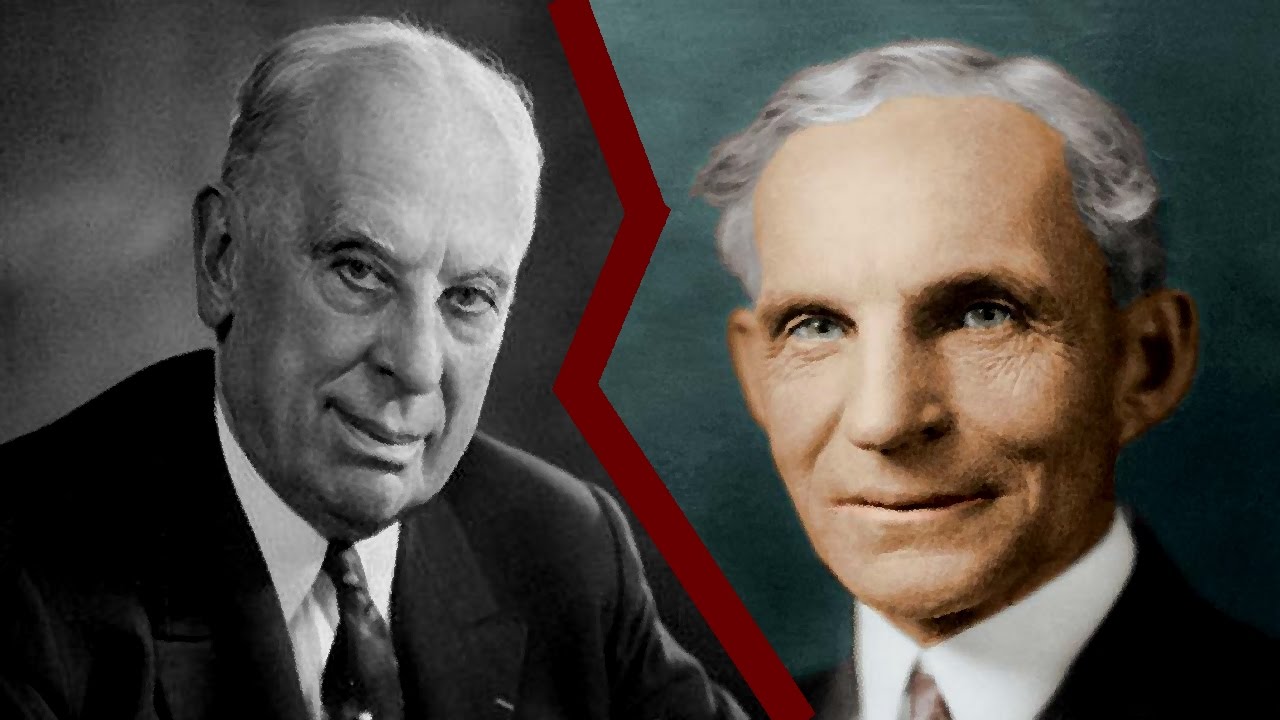

They were the most successful industrialists of the 20th century, but their philosophies were poles apart. For Ford the car was everything: a means of improving welfare and achieving global peace. For Sloan it was merely a product: “the primary object of the General Motors corporation is to make money, not just to make motor cars.”

Contradictions are hardwired into humans. We are natural born worriers – to prevent harm from unknown threats – but we’re also wired for curiosity; a trait that gave our ancestors access to new sources of food, water and tools. This is why we can love and loathe uncertainty, depending on the context.

Nobel Prize winners, scientific geniuses in their own fields, have scientifically questionable views in other fields. Alfred Russel Wallace, codiscoverer of the theory of natural selection, advocated spiritualism and believed that nonmaterial forces explained the evolution of the human mind. Percival Lowell, a pioneer in planetary astronomy whose observations paved the way for the discovery of Pluto, was convinced that he had discovered martian canals of intelligent origin.

It’s a common piece of advice to juniors entering the workplace: the best way of getting stuck in and learning from those around you. At the same time, people love to cite Steve Jobs’ teaching that “innovating is saying no to 1000 things.” The reality is that both have merit – it just depends on the context.

When a journalist watched the world’s best at Wimbledon, he noticed the differences in their warm ups. Nadal was aggressive, sprinting up and down like a man possessed. Djokovic was calm, measured and scientific with every shot. And when Federer warmed up, he was giggling, doing trick shots and exploring his own creativity. There is no right way of doing it – each style worked for the individual.