The 2025 Washington plane crash showed that air traffic control is run by people not numbers. On the day, only one air traffic control worker was managing the Reagan National Airport tower – a job normally done by two people – which meant they were unable to co-ordinate all relevant departures safely. In fact a separate analysis has shown that 90% of all US airport towers are understaffed.

Humans behind the data

Numbers are objective, but the people who make them are not.

Amazon Fresh stores allow customers to purchase items without checking out – supposedly using built-in sensors to track what they’re buying. In reality, as we now know, purchases are manually monitored by hundreds of Amazon employees.

Citigroup accidentally credited a client account with $81 trillion instead of $280. The system requires employees to manually enter the transaction, but (bizarrely) the amount field comes pre-populated with 15 zeros – which the employee forgot to delete. (Thankfully the error was quickly spotted and rectified, not that Citigroup could afford that payment anyway.)

The government only knows how many people are working because of the ONS Labour Force study, a monthly survey that asks thousands of individuals about their employment status. But declining survey response rates means there are now serious questions about data accuracy. We now face a remarkable situation where Andrew Bailey, governor of the Bank of England, says he wishes he “knew more exactly what our unemployment number was in the UK.”

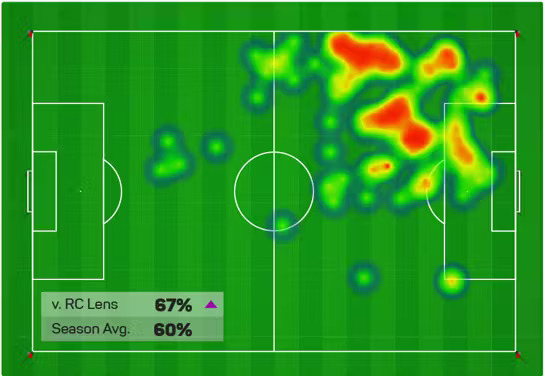

Football clubs use increasingly complicated statistics to assess performance, such as blocks made and touches in the opposition box. But all the data comes from analysts watching games in real time. They note every event that takes place – capturing over 2000 per game – and spend hours re-watching games to ensure quality control.

We still don’t know how many homes are built in the UK each year. Housing data has historically come from the National Housebuilding Council (NHBC) – an organisation established to provide warranties on new homes. But NHBC’s market share has deteriorated in the last few years – from 85% to 60% – which means a significant proportion of homes aren’t counted. By comparing to other records, like council tax, it’s estimated that half of new homes in London were missed in 2023.

To calculate inflation, the ONS uses a typical basket of goods to work out the rate at which costs are rising – but the average doesn’t reflect most people’s experience. Restaurants have a strong weighting on inflation, but really they have little impact on elderly people who don’t leave the house. Meanwhile cigarettes have a weak influence on the score, but tell that to the chainsmoker who buys a pack a day.

What’s worth £99.2bn a year according to one trusted source and £147bn to another? The UK grocery market. Some sources rely on EPoS (electronic point of sale) data – every transaction a retailer has made – but Aldi and Lidl famously don’t share this data, leaving out a huge chunk of the market. Others rely on consumers scanning barcodes of items they’ve bought, but this only covers products that are brought home after purchase and excludes products consumed outside the home after purchase.