We all know that asking someone to keep a secret only invites them to share it. So ahead of the 2012 Olympics opening ceremony, artistic director Danny Boyle subtly changed his request: asking spectators who saw the rehearsal to “save the surprise.”

Magical language

Words don’t just describe our thinking. They shape it too.

John Lubbock wanted workers to have more holidays throughout the year, but MPs were industrialists and unconvinced workers needed more time off. So he proposed the “Bank Holiday Bill”, knowing that banks needed to close at various times during the year, and if the banks were formally closed no business could be done: “If we had called our bill the “General Holiday Bill” or the “National Holiday Bill” I doubt that it would have been approved.”

Consider these two statements about lung cancer outcomes. 1) The one-month survival rate is 90%. 2) There is 10% mortality in the first month. Although the information is identical, surgery is much more popular in the former frame (84% of physicians chose it) than in the latter (where 50% favoured radiation).

After watching a video of a car crash, people estimate the cars to be going much faster (40 mph) when they’re asked about the cars ‘smashing’ into each other, versus ‘hitting’ each other (34 mph). One simple word has a big impact on our memory.

The Chilean sea bass is a marketing invention. Lee Lantz, a fish wholesaler, wanted a more attractive way of describing the Patagonian toothfish so he could sell it to Americans.

The term ‘consumers’ is used so often that we forget there are alternatives. When we call other people ‘citizens’ instead, we improve perceived levels of trust and fairness. Could this re-frame help us unlock a new way of approaching marketing?

A single word can make a policy significantly less appealing. According to pollster Frank Luntz, 68% of Americans oppose inheritance tax when it is labelled ‘estate tax’, but 78% opposite it labelled as ‘death tax’.

In 1988, the US health department coined ‘Designated Driver’ as part of a campaign to prevent alcohol-related traffic fatalities. The campaign broke new ground when TV writers agreed to insert references to designated drivers into scripts of top-rated television programs, such as Cheers, Dallas, and L.A. Law.

Duolingo employees don’t talk about ‘MVPs’ (Minimum Viable Products) during the design process – they talk about ‘V1s’. The logic? “MVPs often have a lower standard of quality and can be used as an excuse to ship subpar work. V1s, on the other hand, are polished. They may not have all the bells and whistles, but they meet our bar.” A small but subtle tweak that reminds the team to always deliver excellence.

The foam that forms on top of espresso was originally called ‘scum’, and was thought to be a bad byproduct of making coffee. So manufacturer Gaggia marketed it as ‘crema’ to make it sound more desirable.

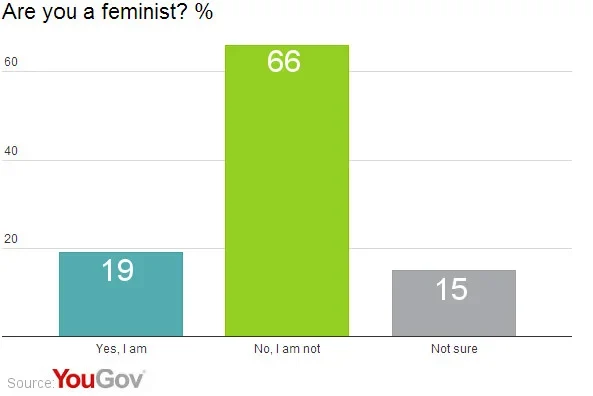

Not all labels are positive. Only 19% of the public identify themselves as feminists, but 81% believe women should be treated as equal in every way.

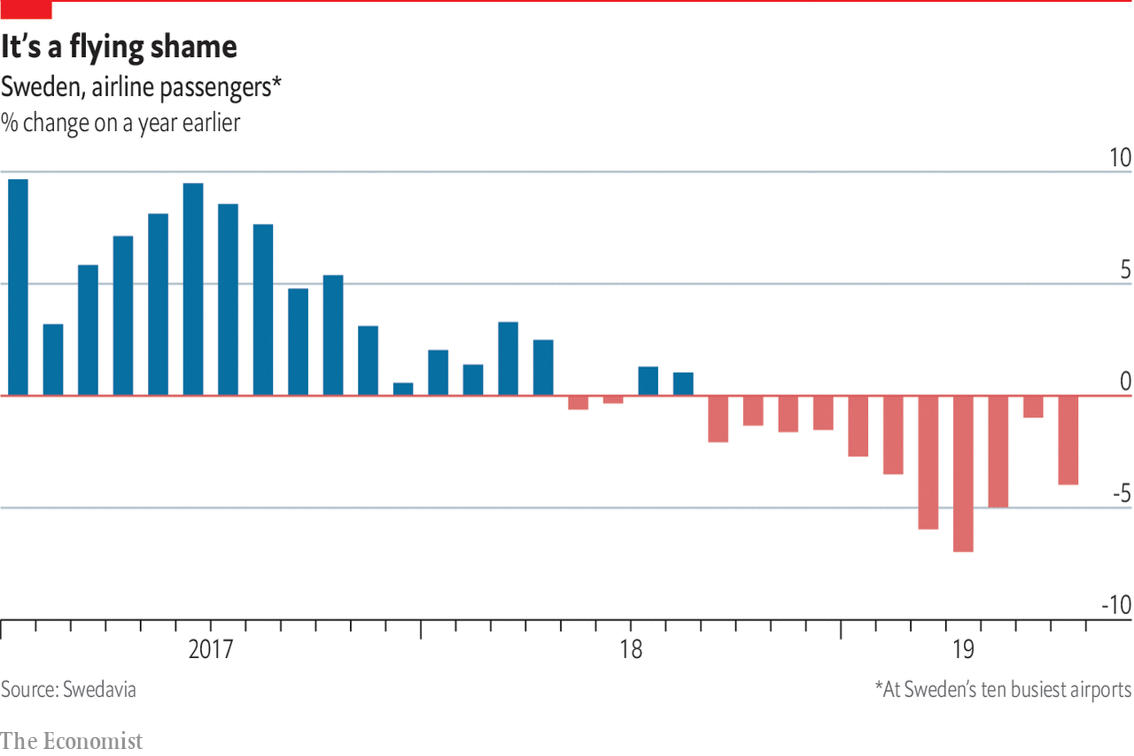

In 2018, Swedes coined a new term, Flygskam, or “flight shame”, to describe the embarrassment that travellers feel about their environmental impact. This phenomenon has helped to decrease passenger numbers by 8%, while train travel has boomed.

In a six-week cafeteria experiment, sales increased with a single evocative addition to the menu; ‘Succulent Italian Seafood Filet’ had 27% higher sales than ‘Seafood Filet’.

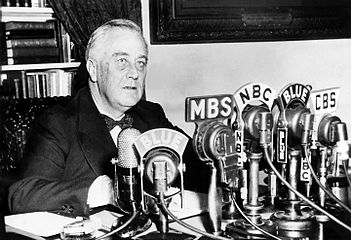

In the 1930s, when America was recovering from the Great Depression and facing the prospect of joining a World War, President Roosevelt created an unconventional communication method. Rather than making big speeches, he used weekly radio broadcasts known as ‘Fireside Chats’, where he explained his policies to ordinary people in their language – using simple words and concrete examples. 80% of the words used were in the thousand most commonly used words in the English language.

Few people recognise this quote: “whenever a government seeks to rely on a previously observed statistical regularity for control purposes, that regularity will collapse”. But it’s actually the original formation of Goodhart’s Law, as described by economist Charles Goodhart. Thankfully, the law was simplified by anthropologist Marilyn Strathern beyond the world of statistics: “when a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”