A mysterious French trader (known as Theo) used an ingenious polling technique during the 2024 US election: rather than asking respondents who they would vote for, he asked them who they expected their neighbours to vote for. This indirect method revealed support for Kamala Harris to be lower than people thought, and Theo was so confident in a Trump win that he bet $30 million on it (a very smart move).

Social desirability bias

We care deeply about what others think.

To gauge the impact of a brand’s ethics on purchase decisions, the most basic approach is to ask people directly, out of context and in isolation. And it turns out that when you do this, the vast majority agree ethics are important. But this finding is at odds with how people behave. Shein & Amazon are incredibly popular retailers, despite their questionable approach to sustainability and taxation. And when pressed, few people can actually name a specific brand whose ethics they admire.

Our desire to please others even extends to our voice. An analysis of interview tapes showed that news host Larry King would (subconsciously) alter his vocal range to match high status guests, like then-president George Bush and actress Elizabeth Taylor.

In a controlled study, people listening to new music liked a song more when they were told it was popular, vs the same song without any extra information. So much for independent choices.

We follow the herd: in supermarkets, top seller labels result in an average sales lift of 41%.

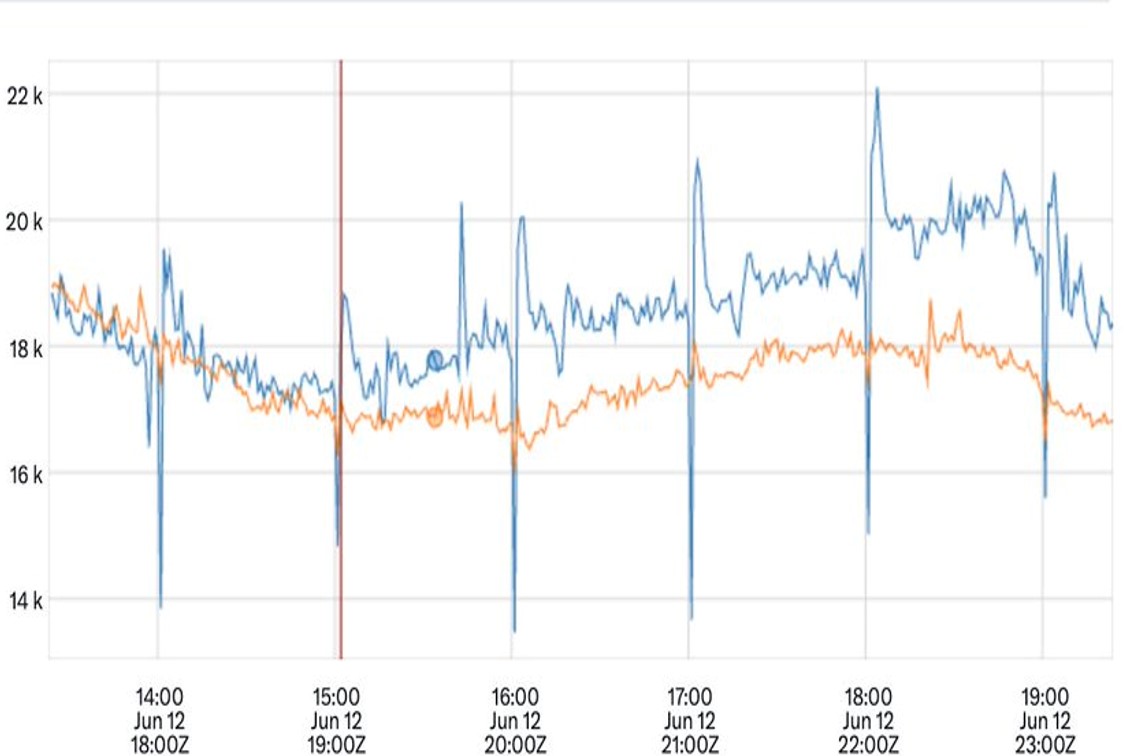

After Twitter / X privatised the likes feature, there was a huge spike (roughly 10%) in their volume – suggesting lots of people have opinions they are happy to express in private but not public.

When someone wins the lottery, it increases the chance of their neighbour going bankrupt: they see the good fortune next door and feel pressure to accumulate more assets of their own, especially flashy purchases like cars, that they simply can’t afford.