During Covid-19, in the absence of in person exams, the government created an algorithm to assign A-level grades. It was designed to be fair – based on historic school results and teachers’ assessments of individual students – but it ended up discriminating against students from poorer backgrounds, whose schools typically performed worse in the past and whose class sizes tended to be bigger.

Work & Education

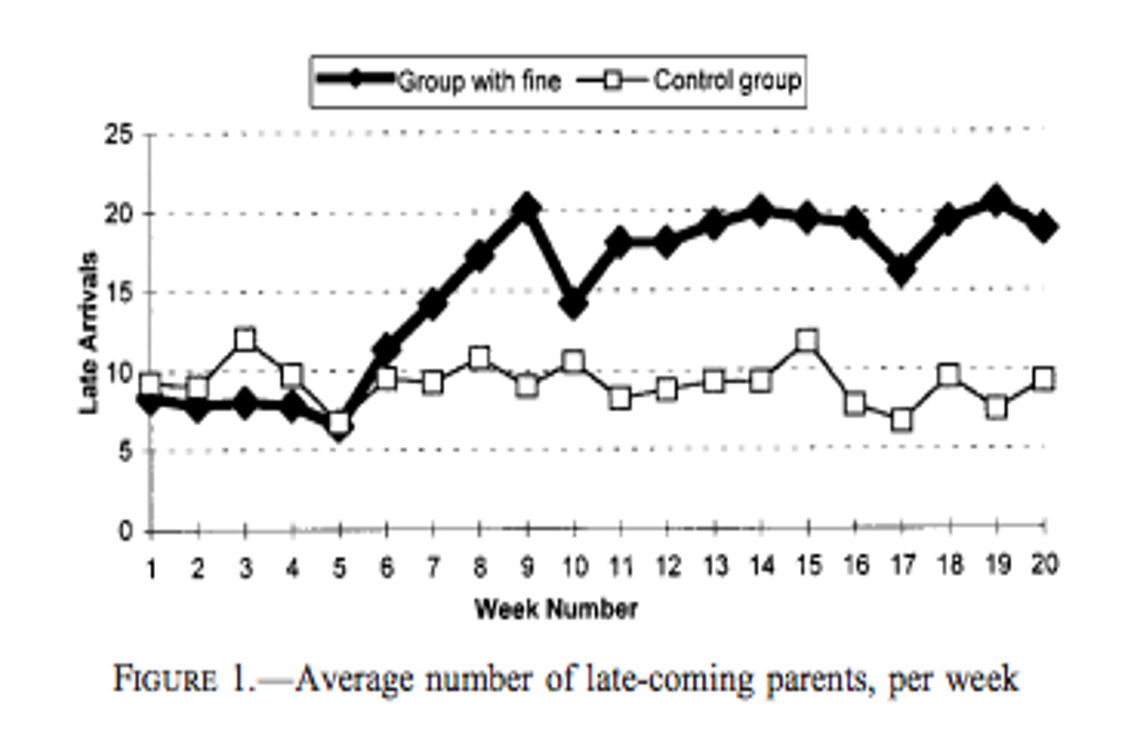

An after-school centre in Israel started fining parents if they picked their kids up too late. But it made the problem worse: late pick ups increased as the fine was now seen as a ‘fee for services’.

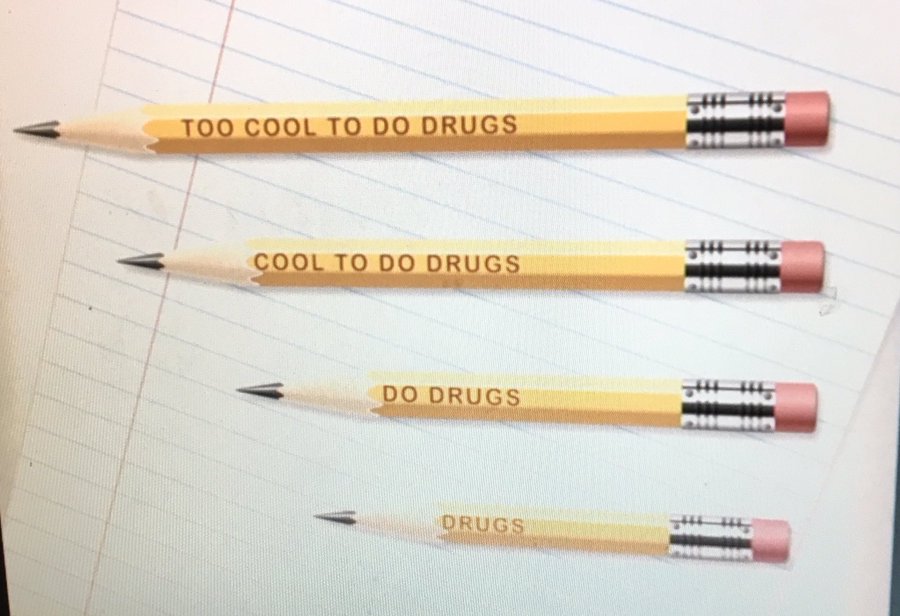

In the 90s, an American charity made pencils with the anti-drug slogan “Too Cool to Do Drugs” but had to recall them because, when sharpened, they read “Do Drugs.”

60% all school book challenges in the 2021-2022 school year came from just 11 people, with sexual content being the main reason behind the challenges.

The US News & World Report started to rank colleges based on many factors, like acceptance rates and class sizes. But colleges quickly started to game the system; aggressively recruiting (and rejecting) candidates to appear more selective, and capping class sizes below the stated suitable amount.

The government only knows how many people are working because of the ONS Labour Force study, a monthly survey that asks thousands of individuals about their employment status. But declining survey response rates means there are now serious questions about data accuracy. We now face a remarkable situation where Andrew Bailey, governor of the Bank of England, says he wishes he “knew more exactly what our unemployment number was in the UK.”

Graduates of top universities earn more in the future, but how much of that is down to the teaching? After all, the top universities are more likely to receive applications from people who are already bright. A US study got around this by analysing students who got into top universities, like Stanford and Yale, but decided not to go. These students didn’t seem to suffer by attending less-selective schools. Apparently, an acceptance letter from Stanford was as good as attending Stanford.

Want to get into Harvard? Make sure your parents went there. Legacy students have a 33% chance of winning a place vs 6% for the rest. (Alternatively, become an elite athlete and your chance of getting in goes up to 86%)

To address the issue of children in India not washing their hands with soap, Savlon created Healthy Hands Chalk Sticks. So when children put their hands under the tap before lunch, the chalk powder on their hands turned into soap on its own – a great example of starting a new behaviour off the back of an existing habit.

It’s a common piece of advice to juniors entering the workplace: the best way of getting stuck in and learning from those around you. At the same time, people love to cite Steve Jobs’ teaching that “innovating is saying no to 1000 things.” The reality is that both have merit – it just depends on the context.

The advent of UK university tables meant that good grades no longer became an aspirational target for marks – but rather a minimum threshold to ward off low rankings. The proportion of English graduates getting ‘good honours’ – a First or 2:1 – has leapt from 47% in the mid 1990s to 79% now. At the same time, England is the only country in the OECD where the literacy and numeracy levels of 16 to 24-year-olds is no greater than that of 55 to 65-year-olds.

During Covid-19 it felt like everyone was working from home. But this was a classic case of marketing myopia. Even at the height of the pandemic, less than half of British workers did so from home.