Forget the million copy bestseller – less than 2% of books manage to sell more than 50,000 copies.

All Threads

Booths, a British supermarket, got rid of its self checkout machines altogether because customers deemed them to be unreliable and impersonal. It turns out that the ‘hassle’ of human cashiers is actually their main benefit. As managing director Nigel Murray put it, “we pride ourselves on great customer service and you can’t do that through a robot.”

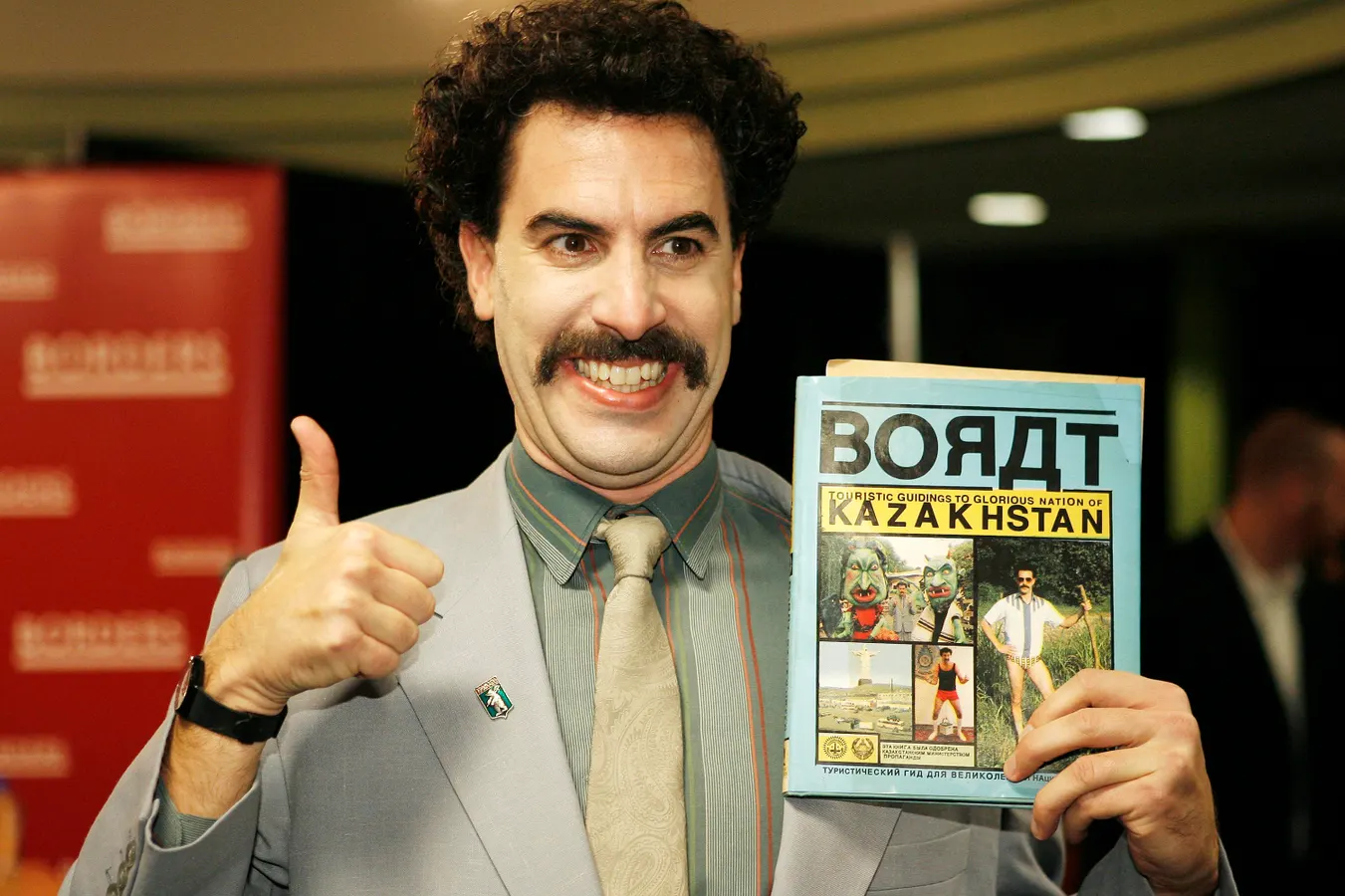

Borat’s depiction of Kazakhstan was not only grossly inaccurate but also offensive. But that didn’t stop tourists planning a trip. Then-foreign minister Yerzhan Kazykhanov admitted six years after the movie’s release that “the number of visas issued by Kazakhstan grew tenfold” before he outlined how he was “grateful to Borat for helping attract tourists to Kazakhstan.”

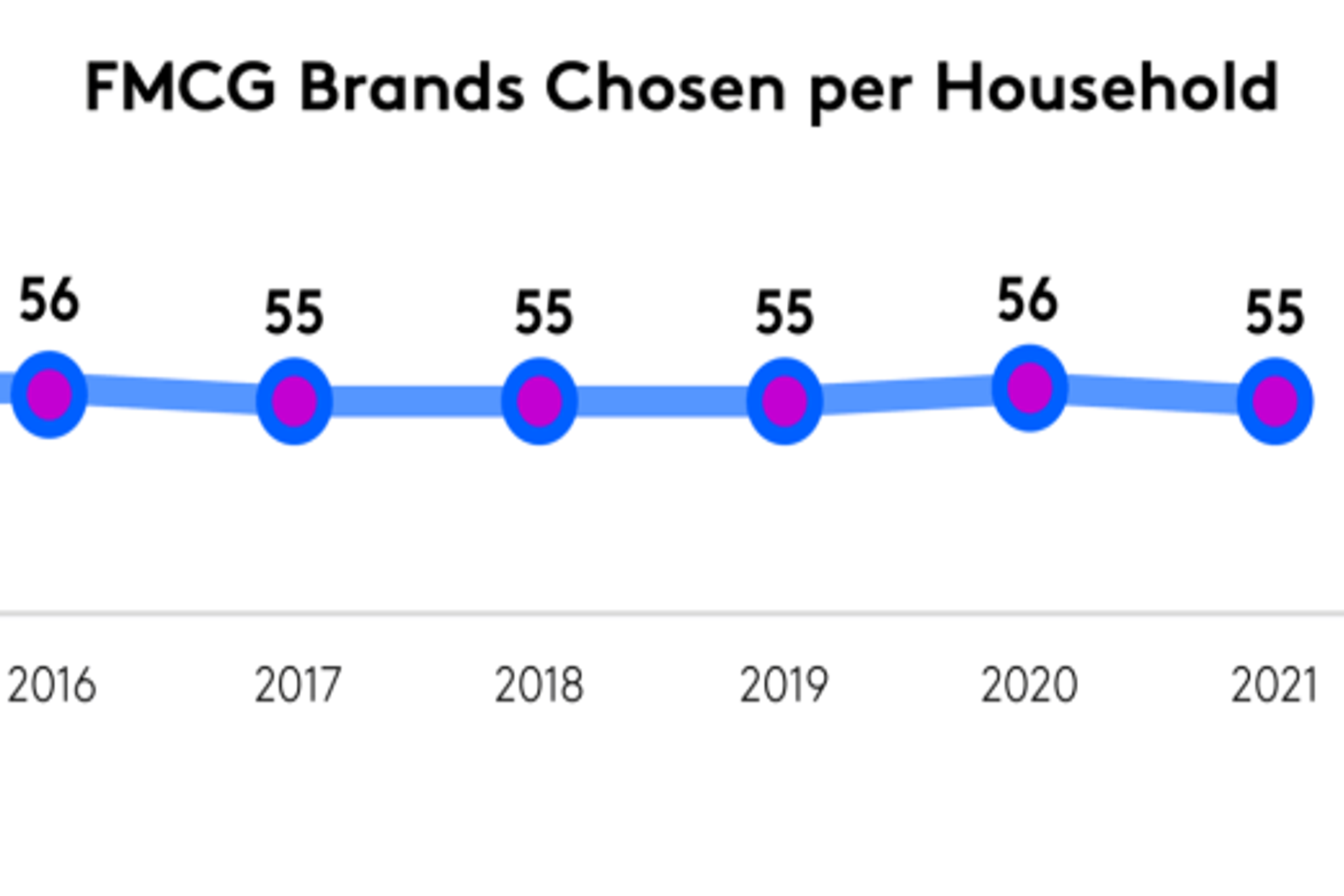

Despite all the technological change over the last decade, our buying habits remain remarkably similar: the average household buys a portfolio of 55 FMCG brands in a year. Of course the brands in question vary from year to year, but the challenge for marketers is still getting into a very limited buying set.

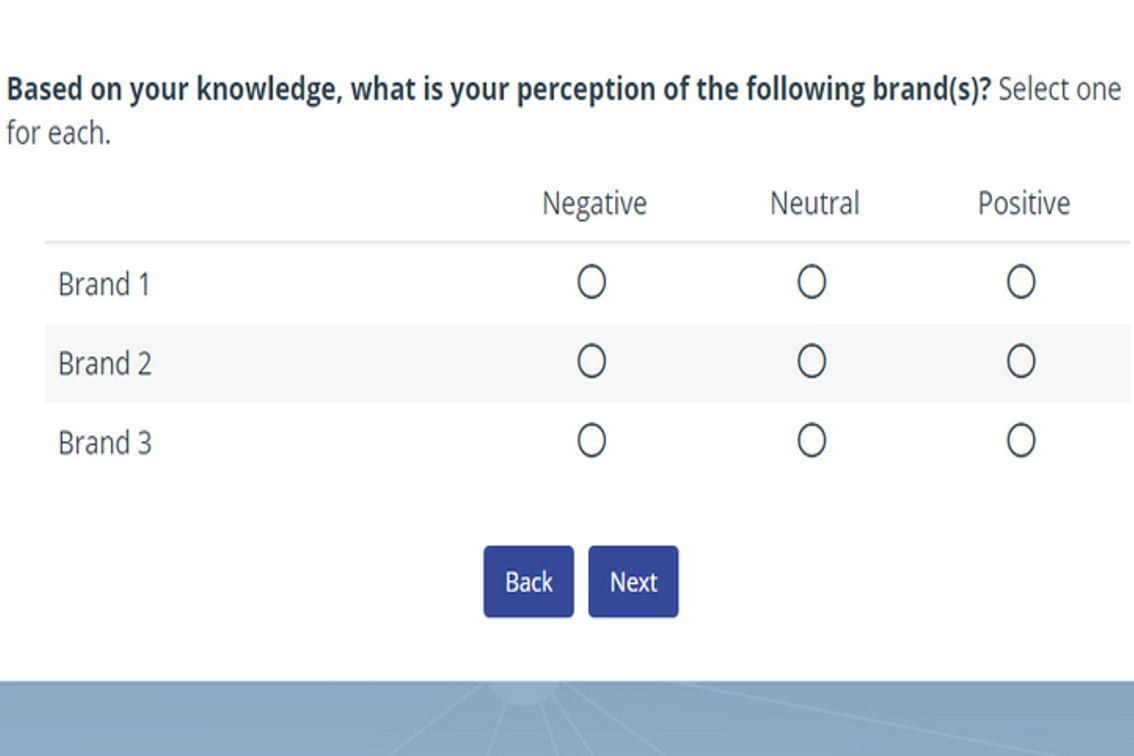

A brand is rated more favourably by those who buy it than those who don’t – simply because those who buy it have more direct experience with it. So when you’re looking at brand attributes (e.g. “it’s high quality) it’s vital to control for market share, otherwise the biggest brands will always do best.

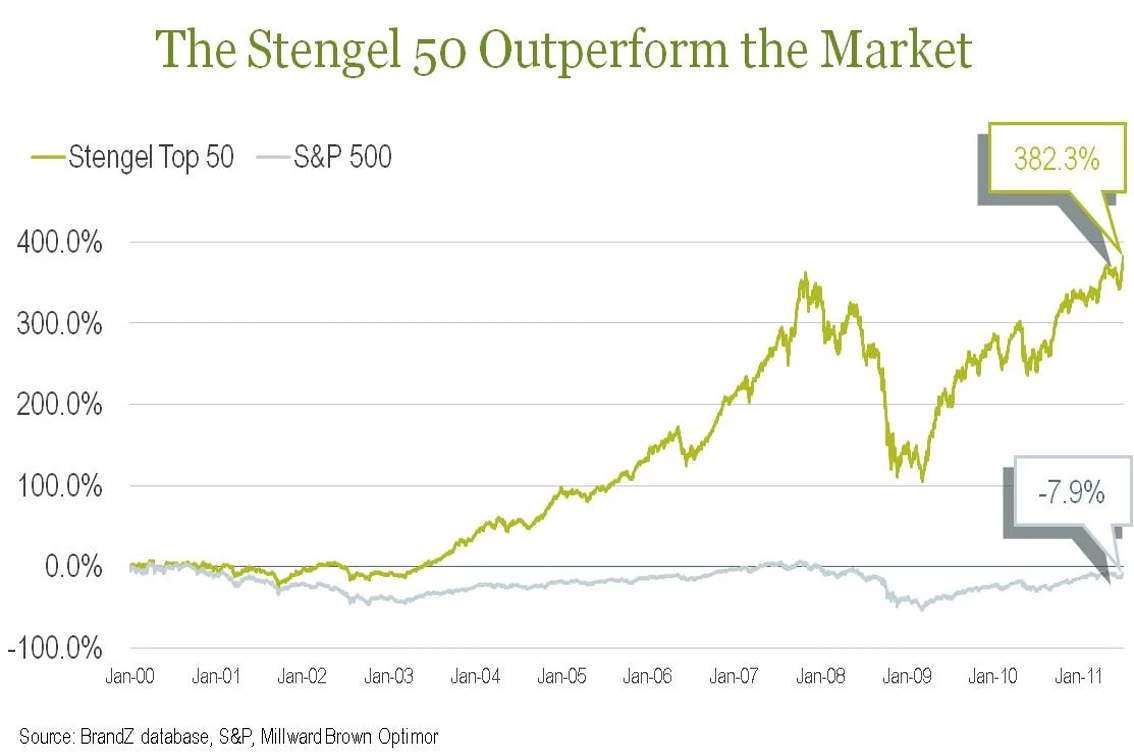

Jim Stengel, ex-CMO of Proctor & Gamble, claimed that the 50 brands with the strongest purpose outperformed the stock market. But as Richard Shotton has pointed out, the data doesn’t stack up: Stengel picked the top 0.1% of brands – period – so purpose has nothing to do with it. Plus, his definitions of purpose were vague at best.

People are 2.5x more likely to switch brands after a major life event e.g. new job, marriage, retirement. (Note, this is based on claimed brand usage).

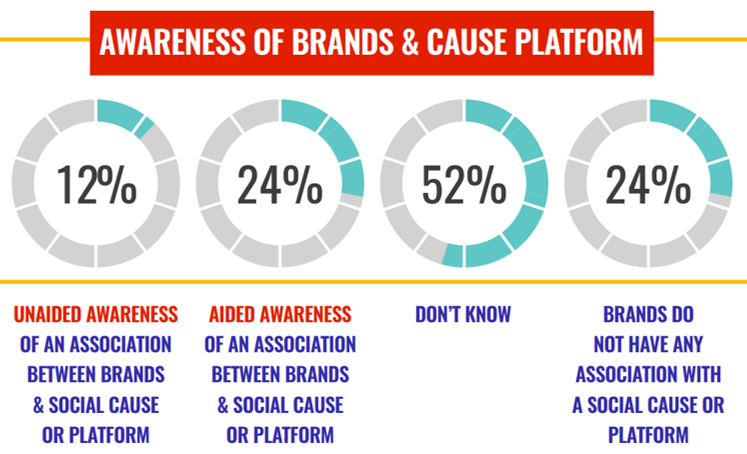

Marketers love to point out that consumers buy brands based on social values. But the truth is most consumers have no idea what these values are. On average, 12% of consumers can spontaneously link a brand to its social cause. And even when shown a list of social causes, only 24% link a brand to the correct one.

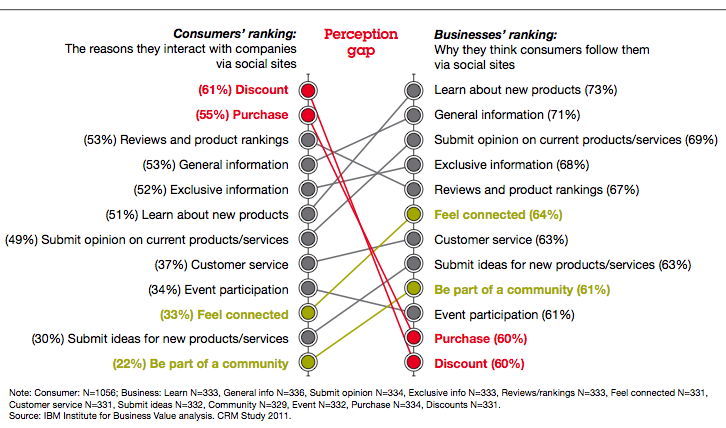

People follow brands on social media to buy products and save money, not to feel deep connection – as marketers assume.

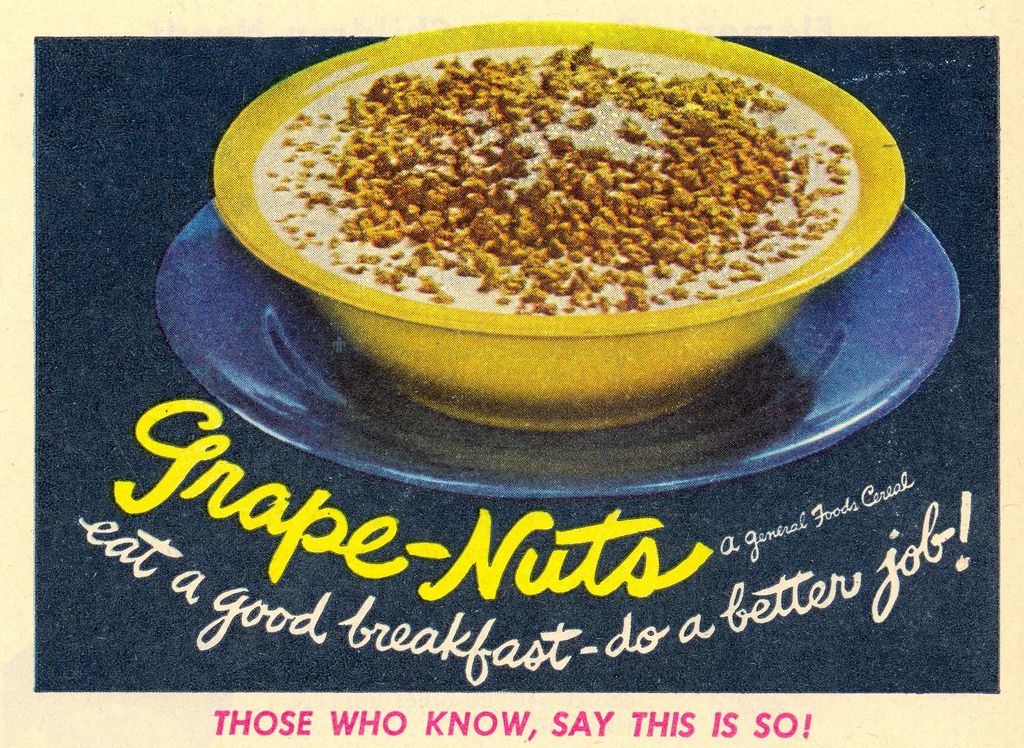

In 1944, a marketing campaign for Grape Nuts would be unleashed called “Eat a Good Breakfast — Do a Better Job”. Radio ads used to say: “nutrition experts say breakfast is the most important meal of the day.” This marketing phrase became soaked into our lexicon ever since.

British Airways make a quarter of their profit (£320m) from Avios points.

Sir Dave Brailsford is synonymous with the concept of marginal gains, having relentlessly pushed the British Cycling team to find 1% improvements;

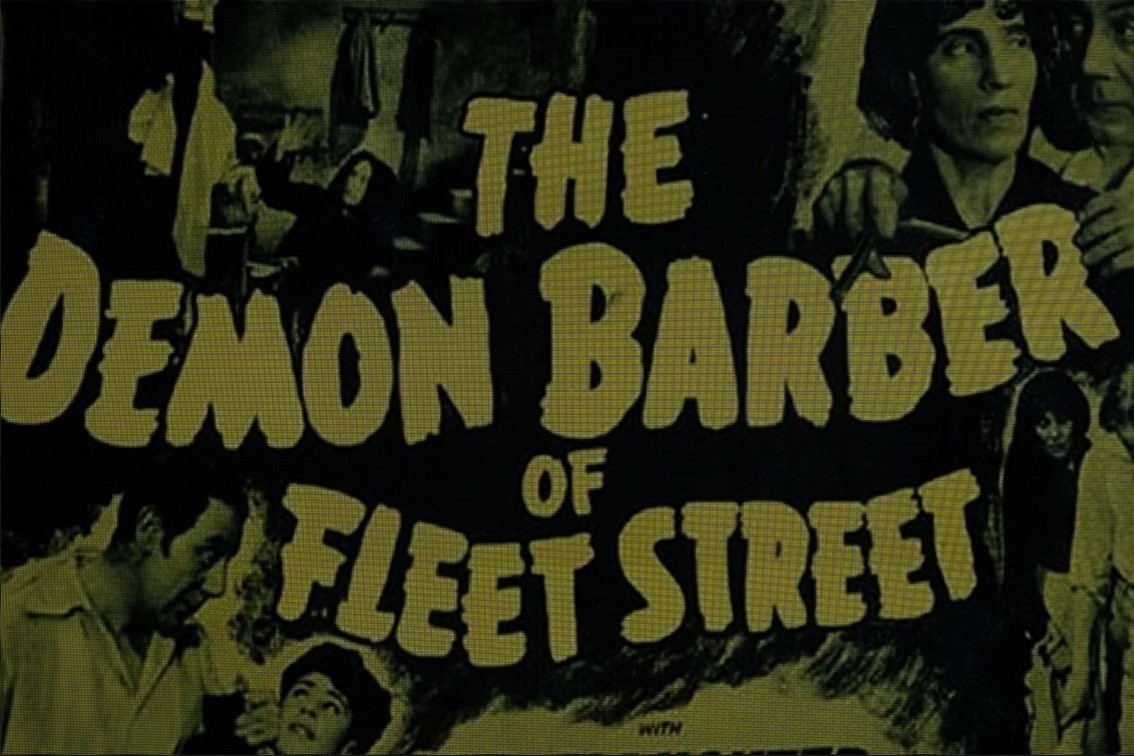

In 1927 British cinemas specified that a proportion of films shown had to be made in Britain. So to avoid losing out, American studios set up production facilities locally and churned out ‘quota quickies’. Many of the films, like the Demon Barber of Fleet Street, were so bad that they were screened to empty cinemas while cleaners cleaned up.

If you’ve ever come up with your Bucket List then you have a film to thank for it. Computer programmers had occasionally used the term in a different context, but its current meaning – the things you want to do before you die – originated from the 2007 film with the same name.

Budweiser had a problem at the 2022 World Cup: Qatar, the host nation, banned the sale of beers. Rather than letting millions of litres of beer go to waste, the brand created a campaign called #BringHomeTheBud, stating that the company would send all the beers to the winning nation. A smart way of standing out and earning publicity during a potential crisis.